|

| Image: wikipedia |

Australian culture is about constantly trying to un-invent the wheel. That’s a paraphrase of a thought written by Australian author John Hughes.

It was at a time when I used to write a lot; I guess that is the whole of my life so it doesn't say much. It was mostly writing from overseas and far from being tech-savvy, I used to rely on e-mail: a long list of potential readers and friends.

It was at a time when I had an Australian government job between trips and there was a colleague of mine; we used to regularly go for coffee at the local café during lunchtimes. It was a pattern that continued for several years though I had changed as many jobs, inevitably in the public sector.

That colleague was on the whole interesting for they had travelled and it was easy to speak of distant places without achieving that puzzled and disbelieving look to be found elsewhere. That colleague had quite a repugnant side too: that is to say they had rather a hatred for Muslims.

When I was younger, even now, there was a tendency to tolerate the intolerable to some degree, for we never really know the reasons behind the irrational beliefs people hold; and given that colleague’s background was not Australian and influenced by a part of the world all too recently in turmoil, I could only wonder how I would react if what had happened far away, in their ancestral backyard, was happening instead in mine. We never really know that do we?

Foolishly I aimed for balance, the redress for psychological scars: in particular by speaking of Bangladesh and all the good, the trivial, the intellectual, the poetic and the inspiring: things that shaped me. Foolishly I underestimated the extent of hatred I was dealing with or the powers behind it. When the words became reprehensible I would close my ears in polite stupidity.

Then one day that colleague said words to the effect of: ‘autopsies are not done well in Bangladesh; when they’re finished the body’s a bit of a mess. In Australia the corpse after an autopsy is well-restored. It makes things easier on the relatives. You should think of your parents, to make things easier.’ I thought my colleague mad at that point.

It was at a time of writing when they said too, about Mr. John Hughes, the Australian author I had never heard of until then. My colleague recommended I read him, said my writing had similarities with his. He had a hard time while writing, my colleague had said, his marriage fell apart and he nearly committed suicide. I didn’t appreciate it as a warning; I never bothered to research Mr. Hughes or read him. Just I remembered the name.

In 2004 we met as usual, sporadic and time to time. Just as I sat at the table my colleague said: ‘I have a friend at ASIO and he says they’re looking for good people.’ ASIO is the Australian version of the CIA and its agenda is the same. ‘That’s nice,’ I replied dismissively and tried to change the subject.

It was a post-September 11 world and I suppose on the one hand ASIO was trying to scramble together some credible knowledge of fundamentalism, Islam in general. They currently plan to double in size and it’s fair to say that from Australian stock there is not much to draw from, in terms of knowledge. There can’t be if they’d thought to ask me.

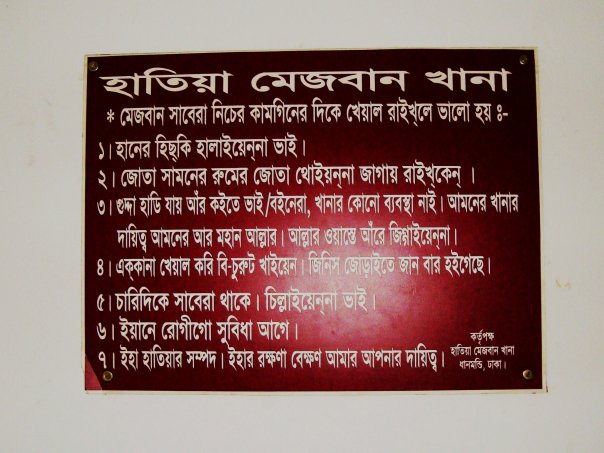

At my dismissive answer my colleague’s jaw actually dropped: I’ve always found security-related people cannot fathom how that’s not the most important sector in the universe; how there are many ways to contribute as a human being. Anyway my thoughts were more about how, after all things, I could ever walk into a tea shop in Hatiya, Bangladesh with an agenda other than adda. That would be obscene. Anyway, no real traveller could ever consent to approaching the big, wide world with anything other than humility and awe: the idea is to extend oneself; the goal knowledge not power. Travel teaches not to take with you a barrow to push.

Recovering, my colleague said, ‘what about the army?’ I made some derogatory statement. ‘Customs?’ The Australian Customs Service: I’ve always thought they did their job well, but it wasn’t my job. Nearly I was amused by the list of suggestions: all security-related, because to some there is nothing else. It was so clichéd. Then came something puzzling: ‘how about the Australian Electoral Commission?’

What a different kettle of fish that was; a true institution of democracy, at least theoretically. In the list it was the odd man out.

It was years later, 2007, when I really considered that. Why the Australian Electoral Commission, from the perspective of security? It certainly couldn’t be any high ideal of democracy, I mean, the Australian security sector had at best stood idly by while Australian citizens were tortured in Guantanamo Bay; they were soon to arrest the Indian, Dr. Haneef, on trivialities potentially designed to increase John Howard’s chances of re-election later that year. ‘Tough on terror’ could have been the slogan.

So I looked at the Australian Electoral Commission’s website and found an answer. As that organisation is responsible for elections in Australia, its employees are obliged not to be politically active or express political opinions. Although it was a time when my then girlfriend was calling me ‘the quiet activist’ it is not something I ever considered; but it seemed to me that it really was the thing. If I would not work for ASIO then I should be otherwise silenced: there are many ways to smother voices. Those were the Howard days.

It was 2007 when I had started a writing course at an Australian university. It was odd for some of the other students tried to tell me to change courses: as a round-about warning. One complained one day, telling me quietly in the car park after class that although they had outperformed others in the assignments they were not being allowed to progress to the second part of the course while others were.

‘Don’t you know about the War on Tolerance?’ I wanted to tell them. For it was that student who said openly in class they had Muslim friends and had talked with them about the anti-Muslim sentiment then rather rampant in Australian society. They had planned to write a class paper on Islamophobia. Like me they were Anglo-Celtic Australian. ‘If you want to progress you need to write some tripe about colonial Australia and create a few heroes where there are none,’ I would have said. But facing my own hurdles at the time, I said nought.

Of note, there was a Muslim in that class; and it’s interesting how the approach differs. In an ‘us’ and ‘them’ world it’s okay for the ‘them’ to take a positive approach to themselves; nobody will listen and they can be managed in other ways. It’s when the ‘us’ make write-crimes, think-crimes about the ‘them’ that it’s all too challenging, that silence is needed; and in Bangladesh corpses after autopsies are messy, says Australia.

We opened our course materials one evening, in class, and there he was: Mr. John Hughes. Australian culture is about un-inventing the wheel, to paraphrase, we read. ‘I don't hear much of him now,’ the lecturer said, ‘I think now he’s teaching at a college somewhere in the Hunter Valley.’ Online it says he’s at a school in Sydney; thing is though, with due respect for education, either outcome as an author makes him sidelined. He did win a prize for his work, so not all is wrong with the world, or perhaps it was given from guilt: his writing remains a little too honest, a little too truthful and a little too Australia-critical. There's not enough goodthink in it.

And what do you think happens when ASIO is refused, when a choice is made to pursue freedom of expression as a citizen of a country without any meaningful protection of the right?

I’d like to take the opportunity, in this country, Bangladesh, one wise enough to have taken steps to include some protection for the voices of its citizens in its Constitution, to commit a few more write-crimes, think-crimes: ‘Bangladesh is not all bad, in fact there are many good things about it;’ ‘Australia is not all good, in fact there are many bad things about it;’ ‘Muslims are not terrorists;’ and ‘better to be a disfigured corpse in Bangladesh than a neat and clean Australian mannequin, for at least one will have lived.’

I take my hat off to you, Mr. Hughes, for your survival.

Indeed, Muslim countries like Iran or Bangladesh make for very nice holidays.

|

| Chinese bamboo book (image from wikipedia) |

Bangladesh Dreaming: Article Index for articles about Bangladesh