|

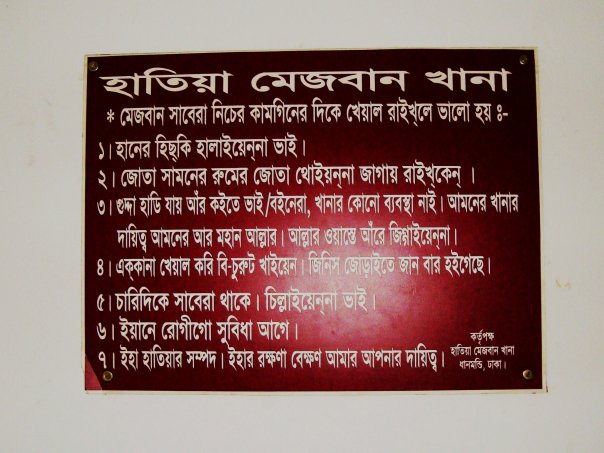

| Mezban Khana sign: 'the rules of the house.' |

There are things that really should not be. Statistically speaking, according to probability and surely taking account of an element of chance as well, being born in Sydney it is altogether unlikely I should be living in Dhaka . It should not be I experienced something of Bangladesh Bangladesh a Hindu country, some version or other of India

But thankfully my life is not that. Yes, I face the Dhaka that we know is part sanely-crazy and part insanely enjoyable. Like the rest of the public I’m in the jams, making the slog home each day, which often involves no less than three rickshaws. I have bills to pay, a household to run and office work which fortunately I love.

And like many Dhakaites I have too that parallel universe called the village: mine is in Hatiya. It’s the highlight of everything: it’s such a privilege when trudging through Farmgate of an evening for example, not to be thinking of whatever tensions the day has thrown at me, but rather, ‘I wonder what’s happening back at the mezbankhana…’

Mezbankhana is the term for ‘guest house’ in the Hatiyan version of Bangla and I use it to describe my Dhaka apartment. There’s a sign I had crafted, just inside the front door, which is a list of ‘rules’ for the place, the Hatiya Mezbankhana in Dhaka . The Hatiyans in particular, also those from greater Noakhali, enjoy that sign because it’s written in Hatiyan Bangla, to the point where some others, from other parts of Bangladesh, can have a little difficulty in understanding all of it at first glance. I had a friend of mine help me write it, and fortunately the craftsman who made the sign was from Noakhali, so when we said, ‘don’t correct the Bangla,’ he understood, amused by its local linguistics.

It was clear from the beginning that the villagers would come, now and then; after all the many years of hospitality they have shown me I’d be offended if they didn’t. It gives great pleasure to reciprocate, which for the first time I can, with an address in the capital. So the Mezbankhana was born.

For the non-Bengali readers, the rules in brief are: don’t spit your betel juice; leave your shoes in front of your room; there is no provision here for food, make your own; no smoking; there are gentlemen in the vicinity, please don’t disturb them; the sick get preference; and the assets of the mezbankhana are for all to enjoy, so please keep that in mind. But it’s the local Hatiyan language that really makes it fun.

It should not be that I have a kind of gramer bari

He was bringing his son-in-law to Dhaka for treatment, my uncle, and as neither of them was familiar with the city they’d gone to the trouble of hiring a guide who knew Dhaka better. As my uncle is a portly fellow there was no chance of getting away with less than two rickshaws for the three of them. They’d told the drivers the name of the hospital alright. What they didn’t appreciate was that like many hospitals, that one had more than a single location; so while the son-in-law and the guide had been taken to the correct outlet, my uncle was taken to another, the one in my street.

He was scared, if the truth be told, not knowing where he was; and to complicate matters his son’s mobile was switched off from being already in the consulting room. My uncle is resourceful; by the time I met him he was chatting away to a stranger with a car who’d agreed to help him and let him stay if needed while his son-in-law was located. How that would have worked out though, who can say?

In my area a good many more people know me than I can name; it’s usual being the odd one out, the bideshi. It’s usual for them to say hello, which my uncle did; and not paying attention I just waved and kept walking. After a few steps it clicked, I did a double-take. ‘What on earth?’

I think the shock was greater for him. Dhaka is after all a big place and what are the chances of getting lost on just my street. Soon enough we were drinking tea at home, back at the mezbankhana. It was such an honour for me that he was there. And suddenly empowered by somewhere to stay, when he did get through to his son-in-law he was able to freely scold him for getting him lost. The following day his son-in-law stayed too.

My uncle’s not the only villager to drop by; normally they arrive in more routine ways: planned. And on the whole Hatiyan people are so polite and sincere, they bring with them such an atmosphere into my home, it’s an altogether better place while they stay. One in three weeks or three in one week, it’s often for medical treatment they come, one of the few reasons Hatiyans will venture to Dhaka, but they also come on crab-business or to attend a cosmetics conference or just for ghuraghuri or tour. My favourite to date was when my Bengali mother stayed over on the way to her familial home in north Bengal . She’ll tell you, in light criticism of her blood-related son my friend, how I remembered to leave a tin of betel leaves with all the trappings by her bed. She’s shown me so much kindness over the years, it’s so rewarding, even for a night or two, to be the host and not the guest.

Once I nearly got in trouble for the mezbankhana; the building secretary was standing in the doorway reading the sign over my shoulder while talking of an administrative matter. His expression went from routine to a frown as he read; he thought I was really running a hotel establishment in the rather nice building! Fortunately my landlords are far more understanding; they know it’s about the more than a decade of Hatiya in my life, of the dear friends and acquaintances with whom those years flew by, even if it was short visits to the island for much of the period.

And so they come, when there’s a little work in Dhaka or passing through… the thing that never changes and though my hospitality cannot possibly match theirs, is that at my place the gramer lok, or villagers from my village, are always, Hatiyan heartfelt, welcome.

And there's always Gilan, if you like hospitality, or staying in a cupboard, free of charge. Or spend some time making pilmeni with Mrs. Val.

This article also published by Star Magazine, here: ...meanwhile, back at the mezbankhana...

And there's always Gilan, if you like hospitality, or staying in a cupboard, free of charge. Or spend some time making pilmeni with Mrs. Val.

This article also published by Star Magazine, here: ...meanwhile, back at the mezbankhana...

|

| Situ and Kaka at the mezbankhana |

|

| Hatiyar lok at the mezbankhana |

|

| Mezbankhana meeting |

|

| Me, Bhabi and the Sahid |

No comments:

Post a Comment