|

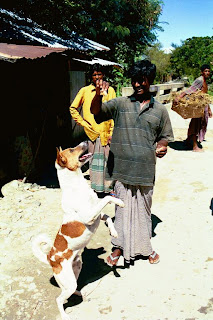

| Mr. Raja Sthan in action, Hatiya, Noakhali, Bangladesh |

The enormous enthusiasm Bangladeshis have for the World Cup is contagious, and for about the first time in my life I am enjoying a sports tournament. As I write they’re about to play, one of the Dhaka home teams, and along with half the city I am hoping for an Argentine victory.

As well as translating are moments of reminiscing, about the three weeks spent travelling in Argentina in 2005. I remember the plate-overflowing slabs of beef, the world’s most delicious, and being confused when buying something and someone said ‘dos pesos’. Without thinking I could and did give ten pesos, because of Bangla, when in actuality they wanted the Spanish two.

More than that, I remember creativity. ‘Give an Argentine a few sheets of art paper, a cardboard box and a pair of scissors and they’ll make a restaurant,’ is what I used to say of the country. Admitted, it’s an exaggeration and admitted, it was a first impression, but from the chiselled splendour of Buenos Aires architecture to the decorations in a café, there always seemed to be a fair amount of art and style in things, and nowhere was that more so than in the small and seemingly nondescript city of Resistencia, on the edge of the Chaco desert in Argentina’s north.

It’s Resistencia that comes foremost to mind because just as the flags fluttering about Dhaka now stoke Argentine memories, so Resistencia’s story took my mind back to the village in Hatiya, Noakhali, for all intents and purposes, this bideshi’s gramer-bari.

I used to go there almost every year, Hatiya, Noakhali, direct from Sydney for a few weeks holiday, to unwind. In 1999 I stayed for six months such that I met all the neighbours, and the neighbour’s neighbours. It was at that time I took for a pet Raja, a cow-patched white and brown street dog.

|

| Villager plays with Raja, Hatiya. |

At first he was nervous, having only just come to terms with being allowed in the house. ‘If there’s a dog in the house the angels won’t come,’ locals said, but my Bengali family used to laugh when they saw him spread out on the living room floor or in the bedroom surveying the yard through the dog-head sized hole he’d chewed in the rusty tin wall.

At first it was controversial, a dog attending the tea shops. Chickens, small goats and the occasional sheep had always wandered freely in and out, under the tables, negotiating customers’ legs. A parrot lived on the table in one of the shops; but dogs were considered dirty. From under the table Raja led theological discussions about dogs and Islam, which on the whole the locals seemed to find entertaining.

Over time and in a typical Bangladeshi accepting style, as Raja’s popularity grew his taboo diminished. I tried to keep out of the discussion and would have tried to keep Raja outside if the locals had asked, but on the contrary his attendance was rewarded with food scraps, shared or, when he’d take directly from customer’s hands as they talked busily and held whatever they were eating at dog height, slightly stolen; but nobody seemed to mind.

|

| Raja relaxes at home. |

That’s how Raja won them. He could stand on his back legs for a minute or more begging for food, mostly he came when I whistled and he entertained when he’d steal my cigarette box and run off down the street with it in his mouth. They’d never imagined a local dog could do these things. He’d make house calls too, travelling alone up to two kilometres to where he’d learnt friends lived, and knocking on the door with his nose, often at night, whenever he was hungry, which was despite whatever I fed him. Dogs are always hungry. Families would let him in, share rice, the women especially excited. ‘So this is Raja,’ they’d say, happy to be introduced to someone they’d heard about.

After a while shopkeepers began to concern themselves with his financial impact, they were after all small businessmen now regularly feeding a dog for free, which they continued to do but quite rightly also established a Raja credit line (to refuse him outright, unthinkable) and as far as I’m aware he was the only non-human to feature in several credit books, running up puppy-sized tea shop bills here and there.

It’s interesting that something similar happened in Argentina. The streets of Resistencia are otherwise ordinary, the architecture unremarkable; the town wouldn’t be much perhaps, but for brothers Efraín and Aldo Boglietti, who opened a culture centre in the 1940s that commenced a Bohemian movement which resulted in Resistencia becoming Argentina’s ‘City of Sculptures’. The city has several hundred sculptures in parks and along its streets. Citizens even get a tax deduction for installing one outside their house.

A nude woman marked one of the main streets, around the corner a bronze girl laughed and adjacent was a man’s bust with a serious expression. Three blocks from the pretty main square was a twisted metal construction, industrial size, being painted red as I watched, or was that part of the art? A bright-vested dog walker approached leading a Dalmation, and there are many dogs in Resistencia – it’s what might be called the Fernando effect.

A small white terrier, Fernando was champion of Resistencia in the fifties and early sixties. The talk of the town, he ate breakfast with the bank manager in his office and was welcome at Boglietti’s centre. When he died, across town shutters closed out of respect and the municipal band played his funeral march.

I was halfway through a pizza lunch when I noticed the upside down table and chairs on the restaurant ceiling. It had drinks, cigarettes still burning with red paper smoke wafting downwards, half-finished food and a stack of cards that had fallen off the table upwards, onto the ceiling – all there just because it Resistencially was. It was after lunch that I found the Provincial Government House; and there, on closer inspection yes, was a modest scruffy dog statue labelled ‘Fernando’, celebrating a much more interesting canine life and for me, linked through the ground at some angle not much removed from ninety degrees, if a little northwards, to the salt-wet sand of a village in Hatiya, Noakhali and its memories of Raja.

And with quirky Resistencia in mind, decorating Dhaka with Argentine and other flags, often in the most creative of ways such as the six storey mammoth flag variety, is an activity that could be considered an apt Bangladeshi tribute, one that is truly and appropriately Argentine.

This article is also published by Star Magazine, here: On Football and Dogs

Another side to travel in Argentina: The Mission

|

| Fernando Statue, Resistencia, Argentina (wikipedia photo) |

No comments:

Post a Comment